Why Emotet's Latest Wave is Harder to Catch than Ever Before

After five months of inactivity, the prolific and well-known Emotet botnet re-emerged on July 17th. The purpose of this botnet is to steal sensitive information from victims or provide an installation base for additional malware such as TrickBot, which then in many cases will drop ransomware or other malware. So far, in the current wave, it was observed delivering QakBot.

In this blog post, we reveal some novel evasion techniques which assist the new wave of Emotet to avoid detection. We discovered how its evasion techniques work and how to overcome them. The first part of the malware execution is the loader which is examined in this article, with an emphasis on the unpacking process. We also partition the current wave into several clusters, each cluster has some unique shared properties among the samples.

Clustering the samples

A dataset of 38 thousand samples was created using data collected by the Cryptolaemus group, from July 17th to July 28th. This group divides the samples into three epochs, which are separate botnets that operate independently from one another.

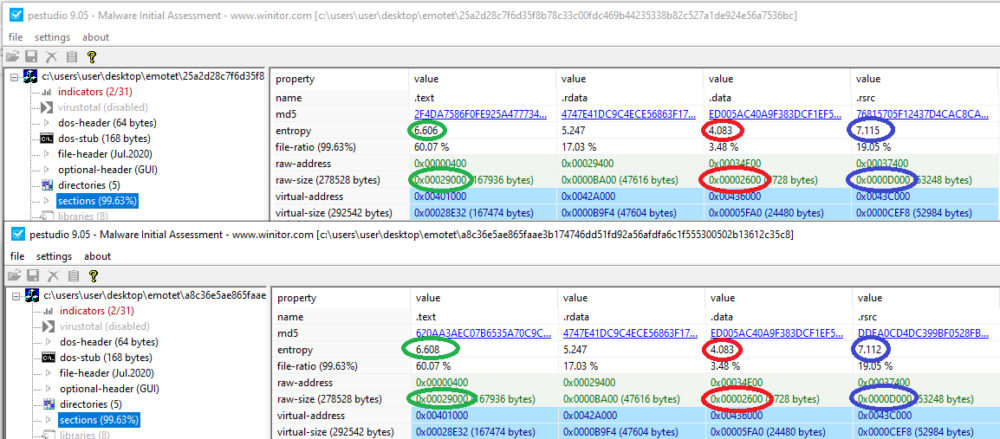

Static information was extracted from each sample in order to find consistent patterns across the entire data set. The information that is relevant to identify patterns includes the size and entropy of the .text, .data, .rsrc sections, and the size of the whole file, so this information was extracted from all the files. We started our analysis with two samples, an overview for which is provided in the image below. By looking at each file size we can see that the ratio of these sections remains the same, and the entropy differs very little between the files.

Image shows different Emotet samples having sections with the same size and entropy

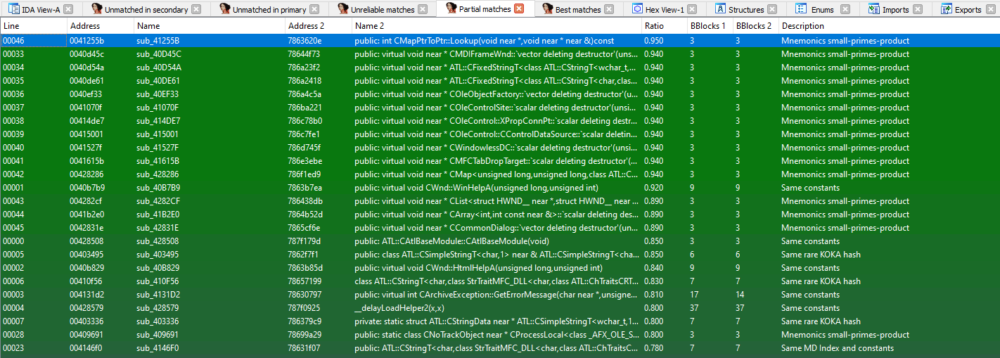

This also results in completely identical code. The two samples presented above were compared using the diaphora plugin for IDA, and all the functions were identical.

Comparing the code of the two samples shows they share the exact same subroutines

Grouping the entire dataset by the size of the files resulted in 272 unique sizes of files. The files matching each size were then checked to see if they have the same static information. This way we discovered 102 templates of Emotet samples.

Each sample in the dataset that matched a template was tagged with a template ID and with an epoch number, as indicated by the Cryptolaemus group. This means that the operators behind each epoch have their own Emotet loaders. The various templates might help reduce the detection rate of the samples used by the entire operation. If a specific template has a unique feature that can be signed, it won’t affect samples belonging to other templates and epochs.

Most packers today provide features such as various encryption algorithms, integrity checks and evasion techniques. These templates are most likely the result of different combinations of flags and parameters in the packing software. Each epoch has different configurations for the packing software resulting in clusters of files that have the same static information.

Identifying benign code

The Emotet loader contains a lot of benign code as part of its evasion. A.I. based security products rely on both malicious and benign features when classifying a file. In order to bypass products like that, malware authors can insert benign code into their executable files to reduce the chance of them being detected. This is called an adversarial attack and its effectiveness is seen in security solutions based on machine learning.

By looking at the analysis done by Intezer on a specific Emotet sample from the new wave, we can see that the benign code might be taken from Microsoft DLL files that are part of the Visual C++ runtime environment. Alternatively, the benign software could be completely unrelated to the functioning of the sample.

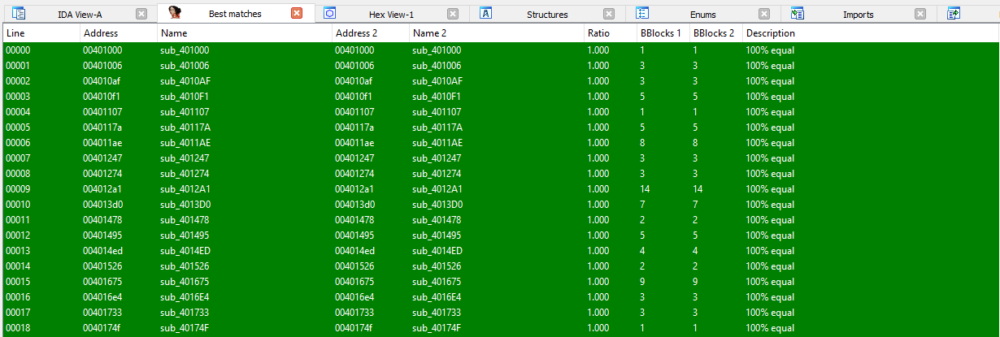

The following screenshot shows the similarities between the previous sample and a benign Microsoft DLL file, using the diaphora plugin:

The Emotet loader contains benign code taken from a Microsoft DLL

Under the column “Name” there are functions from the malware, and under the column “Name 2” there are functions from the benign file. As we can see, the malware contains much benign code which isn’t necessarily needed.

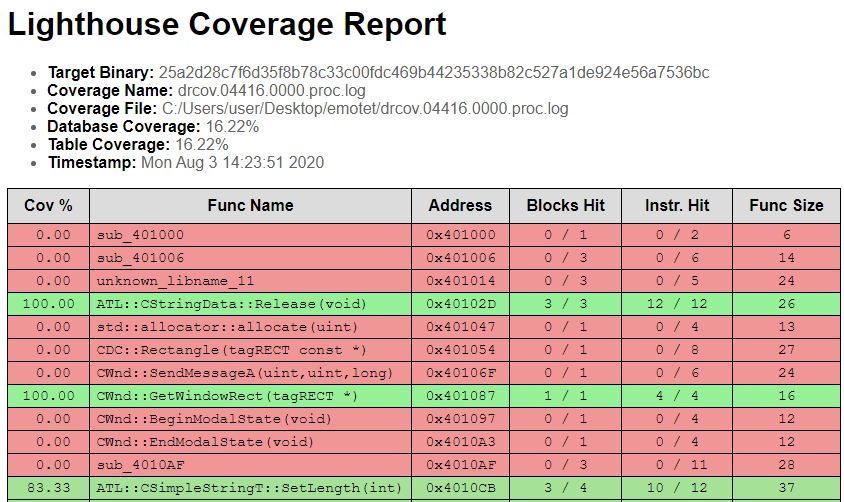

The next step is to check how much of the code is actually used. This can be done using the tool drcov by DynamoRIO. This tool executes binary file and tracks which parts of the code are used. The log produced by this tool can later be processed by the lighthouse plugin for IDA. This plugin integrates the execution log into the IDA database in order to visualize which functions are used. The analysis was performed on the sample shown so far, the result is that just 16.22% of the code is executed

The report produced by the lighthouse plugin showing which functions were executed

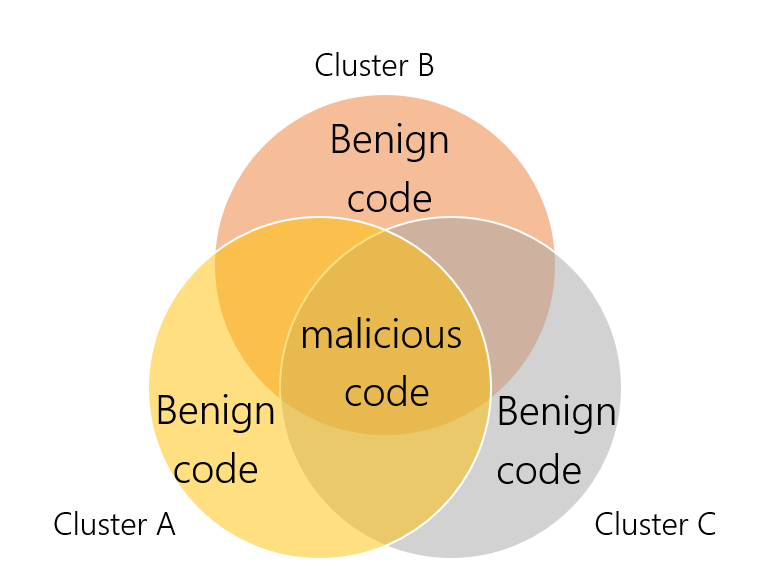

After we filtered out benign code that was injected into the executable, we can compare the code of different variants to locate the malicious functions which exist in every sample.

Diagram shows code from different clusters sharing the same malicious functionality.

Filtering out benign functions helps to reveal the malicious code, but it can also be found using dynamic analysis, which will be discussed in the next section.

Finding the encrypted payload

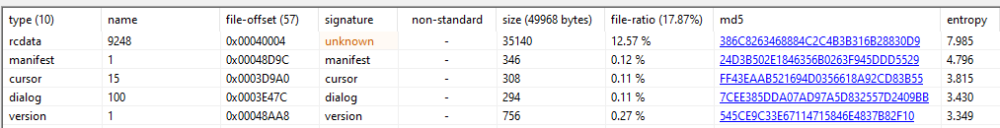

The executable previously shown is an Emotet loader. The main purpose of the loader is to decrypt the payload hidden in the sample and execute it. The payload consists of a PE file and a shellcode that loads it. The encrypted payload will cause the section it resides in to have high entropy. Based on the dataset we collected, 87% of the files had the payload in the .data section and 13% of the files had the payload in the .rsrc section. Tools like pestudio show the entropy of each section and each resource. For example, the resources of a sample with the payload lies encrypted in the “9248” resource:

In order to find the code that decrypts the resource, we can put a hardware breakpoint at the start of the resource.

Pestudio showing the resources with the highest entropy in the Emotet loader

In cases where the payload is inside the .data section, it’s unclear where it starts. We can approximate it by calculating the entropy for small bulks of the section and find where the score starts to rise.

<span style="color: #0000ff;">import</span> sys

<span style="color: #0000ff;">import</span> math

<span style="color: #0000ff;">import</span> pefile

BULK_SIZE = 256

<span style="color: #0000ff;">def</span> <span style="color: #00ccff;">entropy</span>(byteArr):

arrSize = <span style="color: #0000ff;">len</span>(byteArr)

freqList = []

<span style="color: #0000ff;">for</span> b in <span style="color: #0000ff;">range</span>(256):

ctr = 0

<span style="color: #0000ff;"> for</span> byte in byteArr:

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> byte == b:

ctr += 1

freqList.append(<span style="color: #00ccff;">float</span>(ctr) / arrSize)

ent = 0.0

<span style="color: #0000ff;">for</span> freq in freqList:

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> freq > 0:

ent = ent + freq * math.log(freq, 2)

ent = -ent

<span style="color: #0000ff;">return</span> ent

pe_file = pefile.PE(sys.argv[1])

data_section = <span style="color: #0000ff;">next</span>(section <span style="color: #0000ff;">for</span> section in pe_file.sections <span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> section.Name == b<span style="color: #993300;">'.data\x00\x00\x00'</span>)

data_section_buffer = data_section.get_data()

data_section_va = pe_file.OPTIONAL_HEADER.ImageBase + data_section.VirtualAddress

buffer_size = <span style="color: #0000ff;">len</span>(data_section_buffer)

bulks = [data_section_buffer[i:i+BULK_SIZE] <span style="color: #0000ff;">for</span> i in <span style="color: #0000ff;">range</span>(0, buffer_size, BULK_SIZE)]

<span style="color: #0000ff;">for</span> i, bulk in <span style="color: #0000ff;">enumerate</span>(bulks):

<span style="color: #0000ff;">print</span>(<span style="color: #0000ff;">hex</span>(data_section_va + i*BULK_SIZE), entropy(bulk))

Python script that calculates the entropy of small portions of the .data section

Once we know where the payload is located, we’ll be able to find the code that decrypts it, and that is where the malicious action starts.

Analyzing the malicious code

For this part, we’ll look at the sample:

249269aae1e8a9c52f7f6ae93eb0466a5069870b14bf50ac22dc14099c2655db.

In this sample, the script indicates that the beginning of the data section contains the payload although it may vary in other samples. We will put the breakpoint at the address 0x406100. The breakpoint was hit at the address 0x40218C which is in the function sub_401F80. After looking at this function, we notice a few suspicious things:

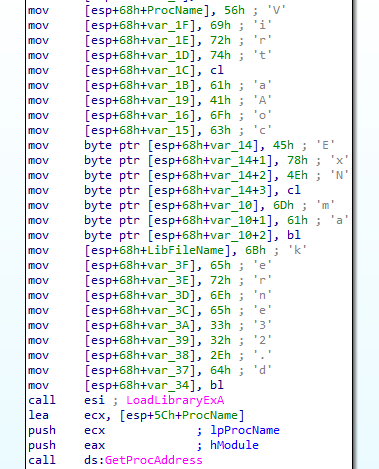

1. This function builds strings on the stack in order to hide its intents. It uses GetProcAddress to find the address of VirtualAllocExNuma and calls it to allocate memory for the payload.

The loader conceals suspicious API calls

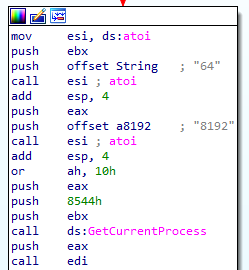

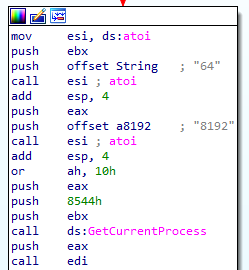

2. It calculates the parameters for VirtualAllocExNuma during runtime, to hide the allocation of RWX memory. The function atoi is being used to convert the string “64” to int, which is PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE. Also, the string “8192” is converted to 0x3000 which means the memory is allocated with the flags MEM_COMMIT and MEM_RESERVE.

The parameters were saved as strings to obfuscate the API call

The payload is then copied from the .data section to the RWX memory (that is where our breakpoint hit). The decryption routine is being called and then the shellcode is being executed.

The loader decrypts the payload and continues to the next step in the execution of the malware

In this blog post we looked at the static information of the new Emotet loader, revealed how to cluster similar samples, and found how to locate the malicious code and its payload. In addition, we exposed how the loader evades detection; primarily the loader hides the malicious API calls using obfuscation, but it also injects benign code to manipulate the algorithms of AI-based security products. Both processes have been shown to reduce the chance of the file being detected. The cumulative effect of these techniques makes the Emotet group one of the most advanced campaigns in the threat landscape.

Update

Read more about the hidden payload in the Emotet loader that is decrypted and then executed to successfully avoid being detected.