Why Emotet’s Latest Wave is Harder to Catch than Ever Before - Part 2

Emotet, the largest malware botnet today, started in 2014 and continues to be one of the most challenging threats in today’s landscape. This botnet causes huge damage by spreading ransomware and info stealers to its infected systems. Recently, a rise in the number of Emotet infections was observed in France, Japan, and New Zealand. The high number of infections shows the effectiveness of the Emotet malware at staying undetected.

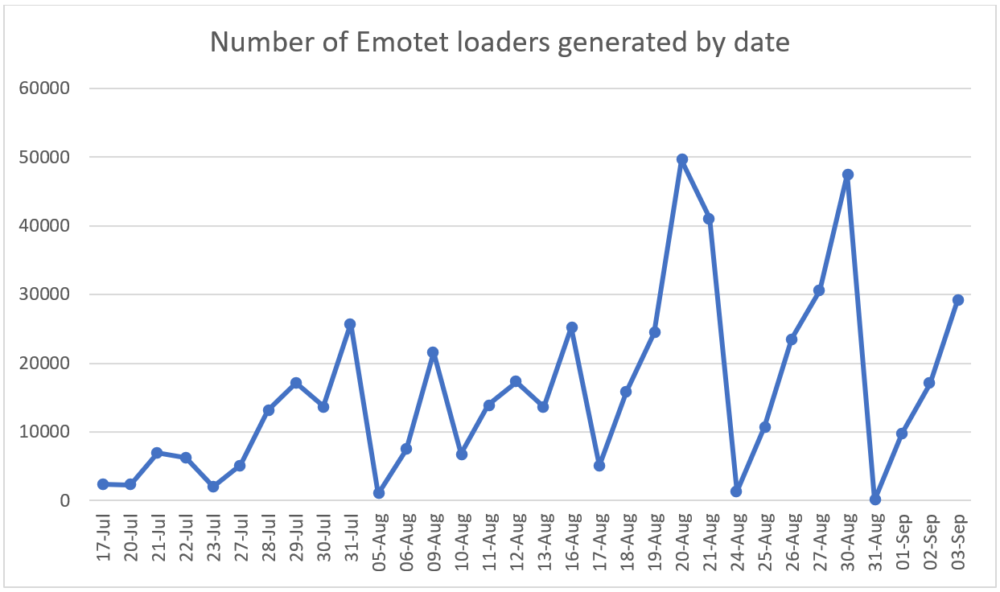

The previous wave of Emotet started in September 2019 and ended in February 2020. The activity was paused for 5 months, and then, on July 17th, the current wave started. The creators behind Emotet are aware that organizations are getting more successful at detecting previous versions as they increase their infection rates. Inevitably, the wave starts to drop as the industry gains a greater understanding and control of the threat.

A point comes when the malware creators realize they need to go back to the lab. For a period of time, they go under the radar completely as they start working on the next wave, making it as potent and evasive as possible. The tactic seems to be working: After going dark for a few months, Emotet appears to have reemerged more evasive than before, this time with a payload delivered from a loader that security tools aren't equipped to handle.

In the previous article, we examined the Emotet loader. We revealed how it evades detection by inserting benign code that subverts security products by obfuscating its malicious functionality. This loader contains a hidden payload that is decrypted and then executed. This payload uses new evasion techniques that were not seen in the loader, and it has some unique indicators that will lead us to the git repository used by the developers to generate their malware.

We collected reports published by cryptolaemus from July 17th, the beginning of the current wave, until September 3rd. Based on this information 444,000 unique Emotet loaders were generated, with the peak occurring at the end of August.

In this blog post, the writer investigates the payload that was encrypted inside the loader, analyzes the next steps in the infection process, and discovers the techniques used to make this malware difficult to analyze.

The Shellcode

In the last step in the execution of the malware, a memory buffer was allocated, and the decrypted payload was copied there. The payload consists of a shellcode followed by a PE file, and an overlay containing the string “dave”. The shellcode performs reflective loading on the PE file by executing the following steps:

- Read the PEB structure in order to locate the APIs necessary for its functionality such as LoadLibrary, VirtualAlloc, VirtualProtect, and more

- Allocate a memory buffer according to the value of SizeOfImage in the optional header

- Copy the image headers

- Copy the image sections and change the memory protection according to the section characteristics

- Retrieve the correct addresses of the functions listed in the IAT

- Perform relocations according to the relocations table

- Jump to the entry point

- Search a function whose name can be converted to the hash 0x30627745 and call it with the string “dave” from the overlay

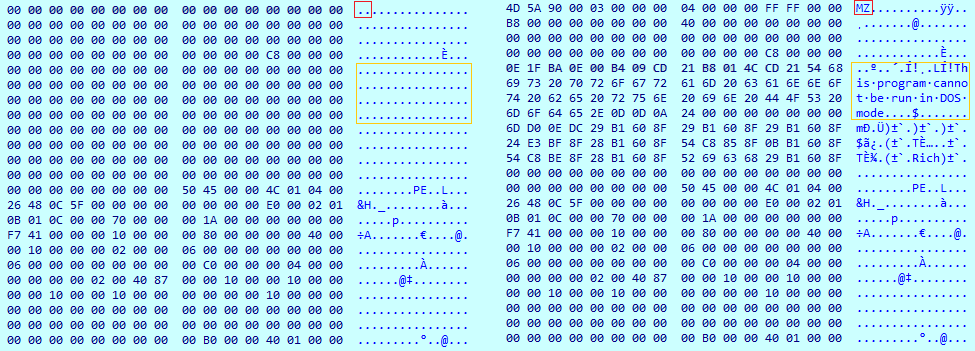

This shellcode utilizes a malicious technique that loads the PE file in a way that makes it more difficult to detect using memory forensics. It replaces the DOS header with zeroes in order to remove strings such as “MZ” and “This program cannot be run in DOS mode”. These strings can be used to detect PE files that were injected into memory.

Memory comparison: on the left is the PE file after it is loaded by the shellcode and on the right is how it should look.

There were a few unusual things about this shellcode:

- The shellcode searched the export table of the file for a function to call although it Isn’t a DLL and it contains no exports.

- The string “dave” seemed out of place and meaningless.

- The hashing algorithm found is common among shellcodes and the hashes of the WinAPI used by the code can be found in online repositories, but the hash of the exported function (0x30627745) didn’t appear there.

Searching these indicators led to the git repository, which contains the source code for this shellcode. We found out that by default the shellcode searches for an export named “SayHello” in the file it loads and “dave” is a parameter that is sent to this function. The Emotet group didn’t change the default parameters in the script and that IOC led to the source code.

Now that we know how the shellcode operates, we can move on to the PE file that was loaded, which is the final payload of the loader.

The Final Payload

Removing the shellcode and the overlay string from the data that was extracted from the loader resulted in this PE file:

D59853E61B8AD55C37FBA7D822701064A1F9CFAF609EE154EF0A56336ABA07C1

Compared to the loader, which was disguised as a benign file, this file has clear malicious indicators:

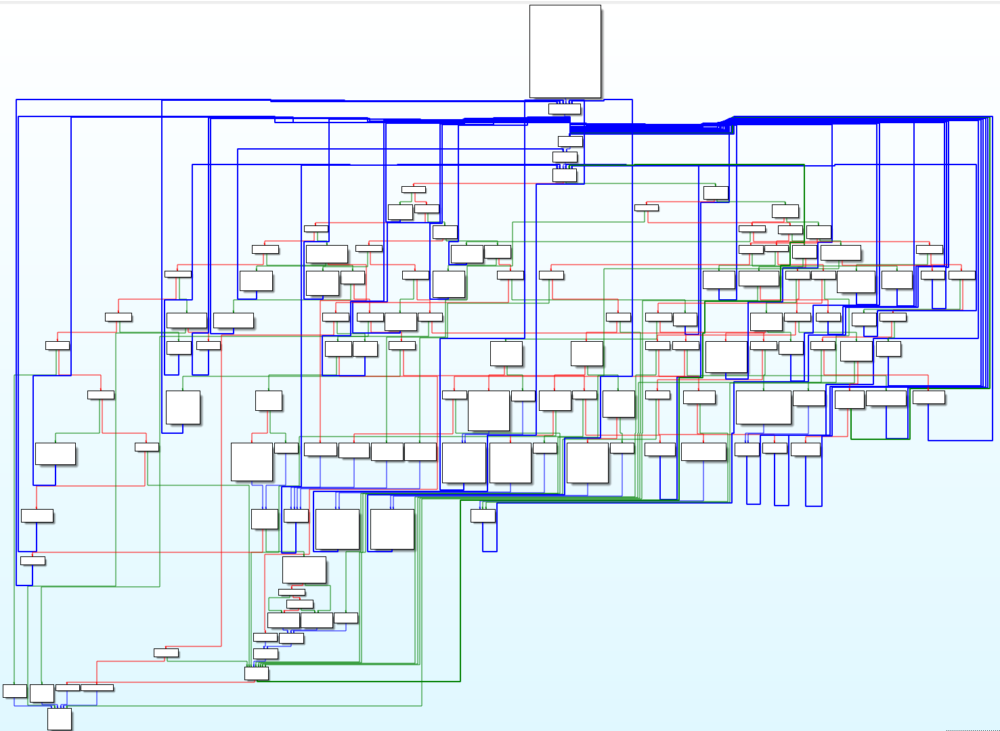

- Code obfuscation – The malware’s developers used a complicated switch case to make the flow of code difficult to understand. It contains many unnecessary jump instructions that make the debugging process longer.

Graph overview of the main function generated using IDA, showing the code obfuscation.

- No strings – After performing static analysis on the sample, no meaningful strings were found. This is because the malware contains encrypted strings and decrypts them only when they are used. When debugging the sample interesting strings were found such as registry keys used for persistence and format strings used for HTTP requests.

- Avoid suspicious calls – Some API calls are known to be monitored by security products since many malware strains abuse them. The malware needs to know if it runs with admin privileges in order to determine how deep inside the system it can install itself. Instead of using the simple API for it (IsUserAnAdmin), it tries to gain a handle with full access rights to the service control manager, which is only accessible with admin rights. This method is less suspicious and might help the malware avoid certain heuristic detections used by security products.

- Empty import table – The malware hides its functionality and intents by not listing any API functions in its IAT. This way static analysis will not help us determine the malware capabilities and behavior. Instead, the malware retrieves WinAPI addresses dynamically.

Much like the shellcode previously discussed, it reads the PEB structure, but it also uses a unique hashing algorithm so standard hash dictionaries for WinAPI won’t help to convert the hashes the code uses back to strings. In order to make the code easier to understand we’ll have to create our own dictionary.

When looking at the disassembly, the hashing algorithm looks complicated, but it contains a lot of mathematical operations that cancel each other out. Using IDA pseudo-code utility, we can convert it to a simple C code. This code was used to create a dictionary with hashes of many DLL files and API names. We wrote a script that uses IDAPython in order to add the name of the dll files and APIs next to the hashes in the code.

<span style="color: #0000ff;">import</span> idautils

<span style="color: #0000ff;">import</span> json

hashes_dict = json.load(<span style="color: #0000ff;">open</span>(<span style="color: #993366;">"emotet_hashes.json"</span>, <span style="color: #993366;">'r'</span>))

dlls_set = <span style="color: #33cccc;">set</span>()

apis_set = <span style="color: #33cccc;">set</span>()

<span style="color: #0000ff;">for</span> func in idautils.Functions():

flags = idc.get_func_attr(func, FUNCATTR_FLAGS)

<span style="color: #339966;"># skip library & thunk functions</span>

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> flags & FUNC_LIB or flags & FUNC_THUNK:

<span style="color: #0000ff;">continue</span>

dism_addr = <span style="color: #33cccc;">list</span>(idautils.FuncItems(func))

<span style="color: #0000ff;">for</span> ea in dism_addr:

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> idc.print_insn_mnem(ea) == <span style="color: #993366;">"mov"</span>:

register = idc.print_operand(ea, 0)

value = idc.print_operand(ea, 1)

<span style="color: #339966;"> # ecx contains the hash respresenting the dll</span>

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> register == <span style="color: #993366;">'ecx'</span>:

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> value in hashes_dict[<span style="color: #993366;">"dlls"</span>]:

dll_name = hashes_dict[<span style="color: #993366;">"dlls"</span>][value]

dlls_set.add(dll_name)

idc.set_cmt(ea, dll_name, 0)

<span style="color: #339966;"># edx contains the hash respresenting the API</span>

<span style="color: #0000ff;">elif</span> register == <span style="color: #993366;">"edx"</span>:

<span style="color: #0000ff;">if</span> value in hashes_dict[<span style="color: #993366;">"apis"</span>]:

api = hashes_dict[<span style="color: #993366;">"apis"</span>][value]

apis_set.add(api)

idc.set_cmt(ea, api, 0)

<span style="color: #0000ff;">print</span>(f<span style="color: #993366;">"{len(dlls_set)} DLLs and {len(apis_set)} APIs were found"</span>)

<span style="font-size: 8pt;">IDAPython script that adds the hidden imports to the code</span>

The purpose of this malware is to send information to the C2 servers about the infected system and receive commands as well as other files to execute. The file contains a list of IP addresses that are iterated over until a response is received from one of the servers.

The malware collects information such as the computer name and running processes, encrypts the data using AES, and sends it over HTTP. The server sends back malware such as ransomware and info stealers that are executed on the infected system.

Summary

In this blog post, we analyzed the next steps in the execution of the Emotet malware. We discovered that the attackers used a publicly accessible shellcode generator, which contained unique indicators. Next, we looked at the final payload of the loader that was responsible for communicating with the C2 servers and downloading additional files. Although much effort was put into making the code hard to understand, we showed how to make it decipherable. By observing the entire infection process done by the Emotet malware, we can see how this botnet achieves going undetected for such long periods.