A Deep Dive into Packing Software CryptOne

Threat actors are continuously developing and refining methods to evade detection from cybersecurity professionals. One of the more creative ways to disguise threat activity comes in the form of packing software – a technique that applies a packing algorithm on malware to produce a file that is harder to detect, analyze, and prevent. While packers are legitimate and quite useful in helping developers protect their code against illegal copying and reverse engineering, in the wrong hands packing software can be used for more sinister purposes.

A packing software called CryptOne became popular recently among some major threat actors. It was first reported by Fox-IT that the group behind Wastedlocker has begun using it, as well as Netwalker, Gozi ISFB v3, ZLoader, and Smokeloader.

The CryptOne packer caught our attention when Emotet started using it. We followed the Emotet group closely and published multiple articles about the malware until the operation was disrupted and taken down. Some of the most recent samples that were generated before the takedown were packed by CryptOne.

As we began analyzing the packed samples we found more malware families that are using CryptOne that weren’t reported by Fox-IT, such as Dridex, Qakbot and Cobaltstrike.

In this blog post we will describe the features of this packer that made it so popular among threat actors, outline the unpacking process, and detail indicators that can determine if a sample was packed with CryptOne.

Features

- Multiple stages

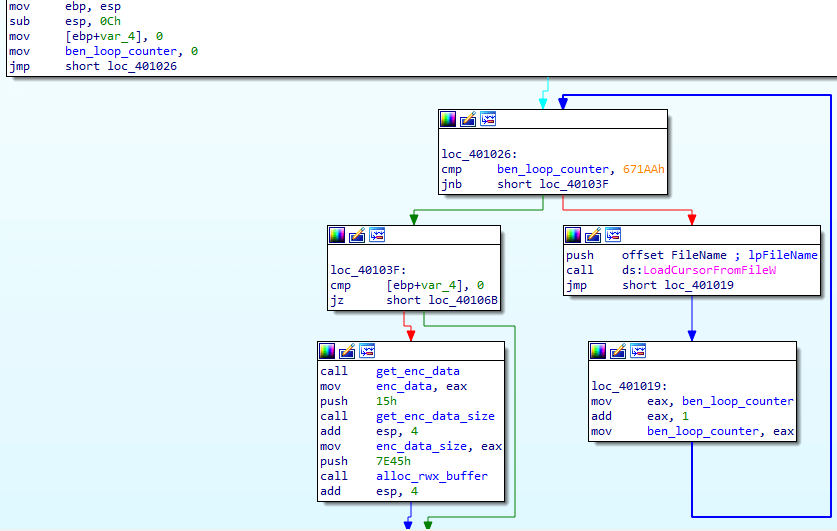

The unpacking process is composed of two stages until the destined malware is executed. The first stage is the DLL that is created by the packing software. This DLL contains encrypted data in one of its sections, which is copied to a RWX buffer and then decrypted. This data contains a shellcode and another block of encrypted data. The shellcode is described in greater detail later.

Beginning of the shellcode after the decryption

Beginning of the shellcode after the decryption2. Reduced entropy

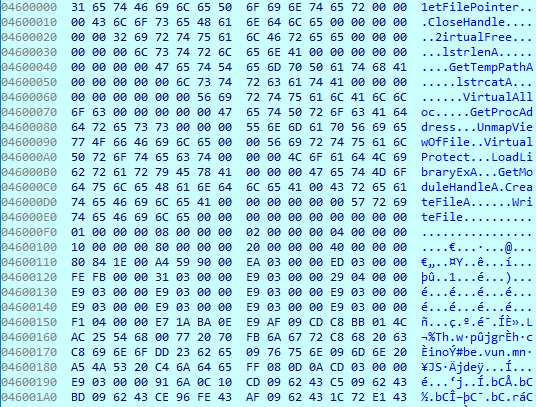

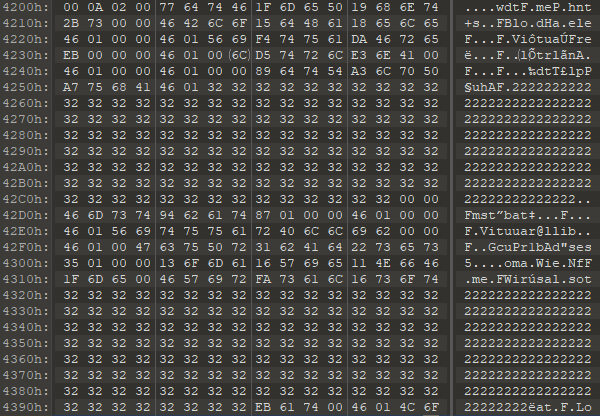

As mentioned, the payload is concealed as an encrypted resource. Encrypted data increase the entropy of the data and causes the loader to look more suspicious. These samples allocate a buffer with RWX permissions, but the encrypted data is not copied to it as is. Rather, it is copied in chunks while some bytes are skipped over. The bytes that are skipped over all have the same value. The reason for that might be to make the reverse engineering process more difficult, but our assumption is that the padding exists to reduce the entropy of the encrypted data and make the loader less suspicious.

Encrypted data padded with chunks of the same value.

3. Sandbox evasion:

Sandboxes let the malware execute for a limited time. If the malware stays inactive until the analysis is finished, it could avoid detection. Sandbox solutions are aware of this problem, so they don’t allow the Sleep function to be used for extended periods of time.The loader created by the CryptOne software simulates Sleep. It contains small chunks of useless code that runs in loops and performs system calls that are irrelevant for the malware's functionality. In some loaders, this code executed very quickly, but the Emotet loaders took almost a minute to execute this code.Another explanation for this behavior is to fill the sandbox report with useless information so it will be harder to spot important alerts. Usually, each system call is logged by the sandbox and added to the report. The packer performs many system calls to create a report that will be difficult to process.

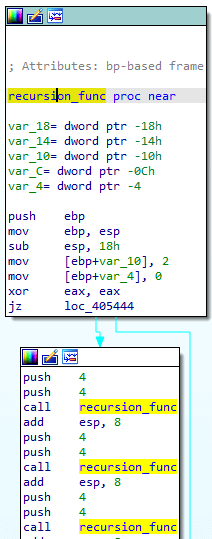

4. Static analysis subversion

: The loader attempts to break static analysis by inserting code blocks that will never be executed and won’t interrupt the unpacking process but might confuse some disassembly algorithms. For example, a function that contains infinite recursion that will always be skipped over.

5. Killswitch

This characteristic was reported by Fox-IT

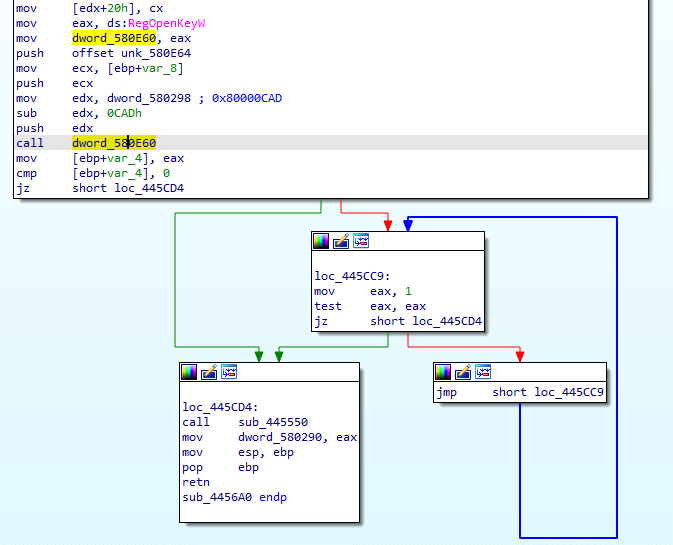

The loader checks for the existence of the registry key: interface\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07}

The loader then enters an infinite loop if the key does not exist.The loader attempts to hide the parameters that are sent to RegOpenKey. An arbitrary value is stored in a global variable. This value is then copied to a register and decreased to reach the actual value that is required for the API call. This technique was observed in multiple families. Also, in some samples the string of the registry key was decrypted in run-time.This killswitch might be a precaution to avoid infecting the control servers. Another killswitch was found only in the Emotet loaders. It exits if it is executed under the user “JhD.”

The Shellcode

The data that is decrypted by the loader has the following structure: names of WinAPI, encrypted PE file, and then the shellcode. The shellcode decrypts the PE which is the destined malware, and then performs reflective loading using the following steps:

- Resolve the addresses of the WinAPI names. This is performed using the DLL kernelbase. This is unusual as most shellcodes use kernel32. This might be to evade detection by security products since it is known that many products place hooks inside functions from kernel32.

- Unmap the loader image using UnmapViewOfFile. This is another uncommon technique. Usually, a new buffer will be allocated at a random address, but the shellcode of CryptOne attempts to copy the destined malware to the same address that the loader was in.

- Copy the PE headers and sections

- Fix the Import Address Table with the correct addresses

- Perform the relocations listed in the relocation table

- Change the memory protection of each section according to its characteristics

- Update the following fields in the LDR entry of the image: entry point, DLL base, and size of image

- Update the image base address field in the PEB structure

After all these steps are performed, the shellcode jumps to the entry point of the destined malware.

Conclusion

CryptOne is a sophisticated packer and presents a unique set of challenges to detect. It is composed of multiple stages of execution and attempts to evade detection by subverting static analysis, reducing the entropy of the data, and confusing disassembly algorithms. It also tries to avoid sandbox detection and cause damage by staying inactive for a long duration and filling the report with useless information.

These features make it attractive for attackers that need to reduce the detection rate of their malware, and we might see more threat actors use it in the near future.

If you’d like to hear more about our industry-leading approach to stopping malware, please contact us and we’ll set up a demo.

/blog/why-emotets-latest-wave-is-harder-to-catch-than-ever-before

/blog/emotet-malware-2020/